# 10,258

Although we haven’t seen a new avian flu outbreak in nearly a week, anyone who has tried to negotiate a bank loan in order to buy a carton of eggs this month knows the impact of H5N2 remains strong. Even here in central Florida, almost a thousand miles from the closest outbreak, the price of eggs has (in some cases) nearly doubled.

As the summer heat intensifies, the transmission of avian flu decreases. The wild and migratory birds that tend to carry the virus are spending their summer vacation in their far northern breeding grounds, and – for a time at least – poultry farmers and the food industry can expect a respite.

Three, perhaps four months from now, the concern is that HPAI H5 could be back, and this time it could extend its reach into the eastern and southern states as infected migratory birds head south for the winter.

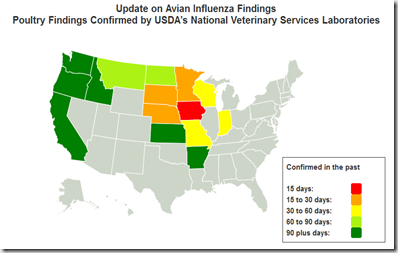

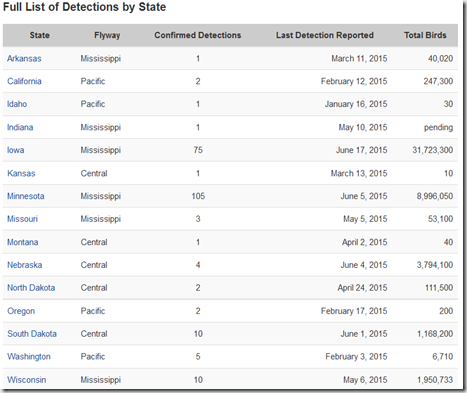

While the first detections of North American HPAI H5 took place in early December of last year in the Pacific Northwest, it wasn’t until March and April that the H5N8 virus (and its reassortants H5N2 and H5N1) began to gather steam in the rest of the nation.

It is likely that this `late start’ in the Midwest limited its impact. Still, the losses, as tallied by APHIS, are considerable; almost 50 million birds lost or destroyed.

In addition the USDA lists a half dozen captive wild birds (falcons, owls) that have contracted the HPAI virus, along with 75 wild and migratory bird detections (see list here).

While no one can be sure who HPAI will play out in North America this fall, speaking before the USA Poultry &Egg Export Council (USAPEEC) last week, John Clifford, the chief veterinary officer of the United States warned the USDA was preparing for a `worst case scenario’.

Agrimarketing.com reported yesterday in USDA CHIEF VETERINARIAN: AVIAN FLU WILL BE IN ALL FLYWAYS THIS FALL, on his comments, which included:

- A worst-case scenario, he said, would involve the highly pathogenic strain of avian influenza returning in migratory wild birds in the fall of 2015 and infections occurring in all poultry sectors - broilers, turkeys and egg layers - and across the country including in the broiler production regions of the Southeastern U.S. and the Upper Midwest and California.

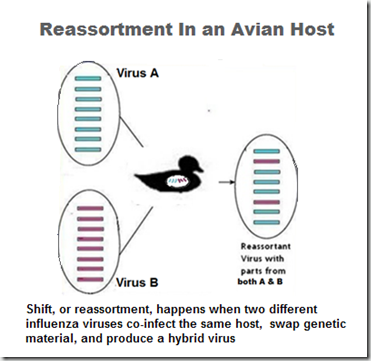

- Clifford said another part of such a scenario is if the H5N2 virus were to genetically reassort to present a different strain than the one presently infecting poultry and wild birds in the U.S.

Stressing the need for better farm biosecurity, Dr. Clifford called HPAI an unprecedented challenge for United States poultry producers. "For the first time, we have high-path avian influenza all around the world in wild ducks. Things have changed and we all need to recognize those changes. This has caught all of us off guard.”

His primary warning was that preparing for HPAI’s return this fall could cost millions, but failing to prepare could cost billions.

While the most likely scenario is some kind of repeat – perhaps worse, perhaps not – of what we’ve already gone through these past few months, the potential that HPAI H5 could evolve into new subtypes or variants cannot be dismissed.

How viruses shuffle their genes (reassort)

The H5N8 virus from which H5N2 and a new (North American) H5N1 subtype have emerged appears to be highly promiscuous, and could well be generating additional viral offspring this summer among the migratory birds roosting in the far north.

While evolutionary changes aren’t always bad (some viruses can attenuate or become less `fit’ as they mutate), they can be unpredictable.

Which is one of the reasons why, three weeks ago, we saw the issuance of a CDC HAN:HPAI H5 Exposure, Human Health Investigations & Response, that provided guidance to state and local officials, and clinicians, on how to handle possible human exposure to HPAI H5 viruses. As they stated in the forward:

While these recently-identified HPAI H5 viruses are not known to have caused disease in humans, their appearance in North American birds may increase the likelihood of human infection in the United States.

The spread of avian flu over the winter of 2014-15 was unique – not only in North America – but around the world. H5N8 made its way from Korea and China to western and central Europe, H5N1 re-emerged in European and African countries that have not seen it in years, and new strains – like H5N6 – continue to emerge in Asia.

In Egypt, H5N1 has not only caused huge losses in their poultry sector, it has sparked the largest human outbreak of that virus since it emerged nearly 20 years ago. While the full extent of that outbreak isn’t known (see Egypt’s Ongoing Silence On H5N1), at least 160 cases have been reported since last November.

All of which has prompted the World Health Organization to issue a warning last February that H5 Is Currently The Most Obvious Avian Flu Threat.

While no one can predict where any of these viruses will end up – as the number of HPAI viruses in circulation around the globe increases - the greater the chances are that someday one will successfully adapt to humans.